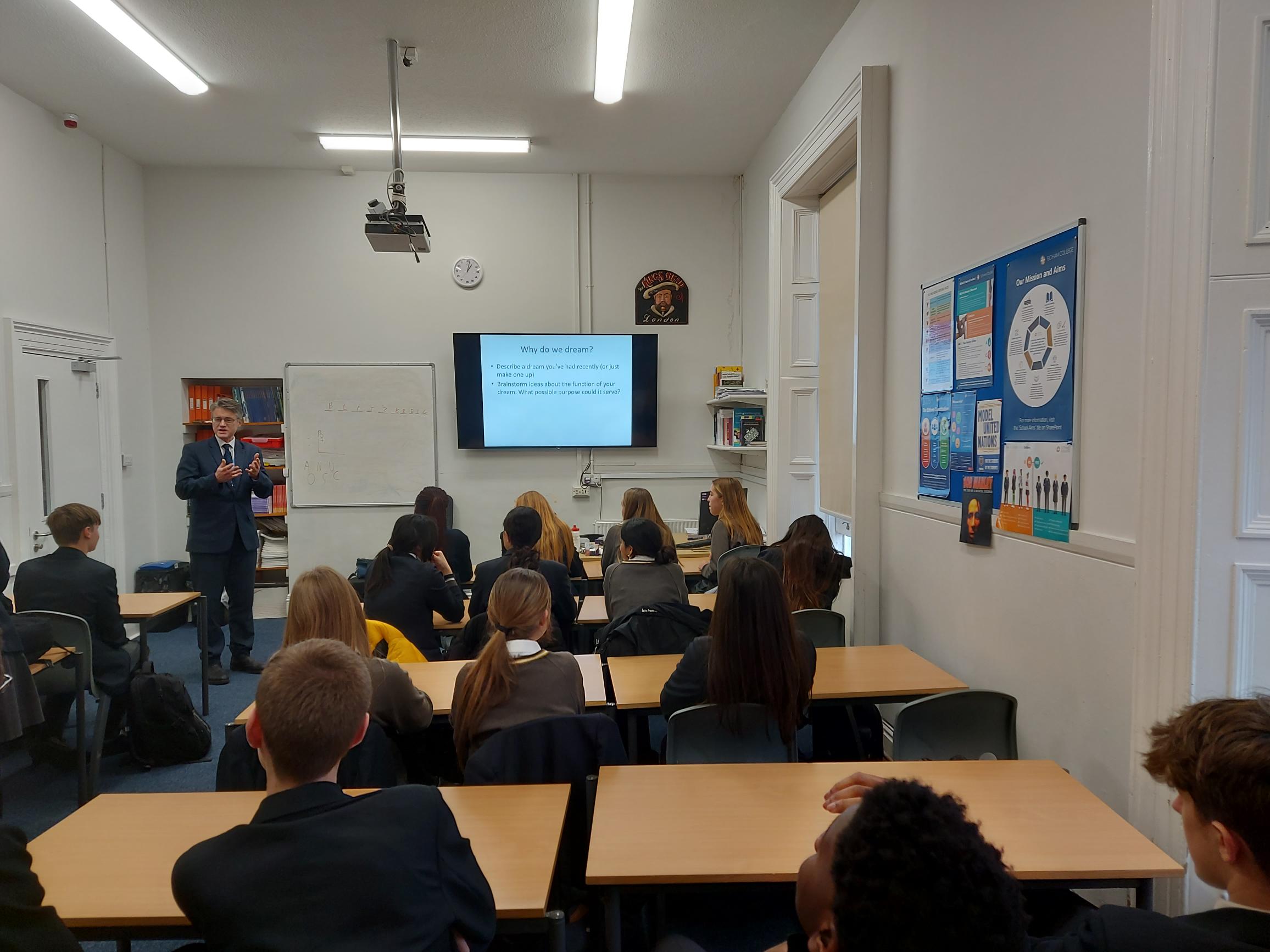

Year 11 Colloquium: Why Do We Dream?

What’s the most bizarre dream you’ve had? What did it mean? Or did it actually mean nothing at all?

In 1953, sleep researchers identified distinct episodes during sleep associated with dreaming. Owing to what they described as a ‘hurricane’ of ocular activity during this phase, they called it rapid eye movement sleep or REM for short. Yet remarkably, almost 75 years on, there is still no consensus over the function of REM or why we dream.

Building on a talk last year about the scientific method, Biology teacher Dr Henry Nicholls gave an overview of several of these alternative hypotheses for the function of dreaming sleep. Given how much time newborn infants spend in dreaming sleep, REM is likely to play an important role in brain development. Recent studies also provide clear evidence of There are several well-known examples of the Eureka-like power of dreams, including August Kekulé’s vision that cracked the structure of benzene, Dimitri Mendeleev’s brilliant periodic table of the elements and Paul McCartney’s Yesterday, one of the most covered songs in the history of recorded music. Dreams might also be the brain’s way of creating a safe, virtual world in which to rehearse dangerous situations.

Or maybe dreams themselves are not as important as we are led to believe. What if they are just the emergent experience of neurological activity that is occurring for some other reason? It’s now clear, for example, that REM sleep plays a crucial role in “synaptic pruning”, a process analogous to editing that involves strengthening the connections between some neurons and weakening or erasing others. Perhaps this is the real function of REM sleep and the dreams we experience are just a mainly meaningless byproduct.